THE DJINN WAITS A HUNDRED YEARS, by Shubnum Khan

The city of Durban on South Africa’s east coast falls psychically somewhere between Miami and New Orleans. It’s sugarcane-sticky and portside-seedy, a little glam, a little Miss Havisham. Add vervet monkeys and a turbulent colonial history and Durban Gothic should already be its own genre. That it’s not means Shubnum Khan gets to set the tone with her magical and only gently haunted haunted-house novel, “The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years.”

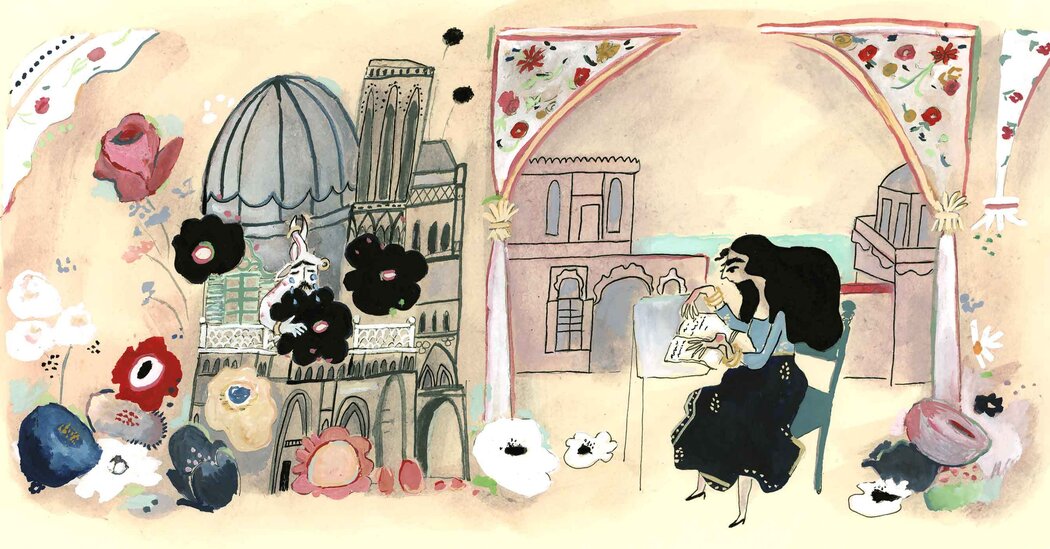

The abode in question is Akbar Manzil, dreamed up by Akbar Ali Khan, newly arrived from India and determined to build a life in South Africa with his dismayed wife, Jahanara, who dreams instead of England. Akbar believes that “beauty is not a need but an ecstasy,” and his grand folly is a mishmash of influences, with “Gothic towers, Islamic arches and European balconies” and an exotic menagerie in the lavish gardens, including a giraffe and a lion that roams free on Sundays.

Once a marvel rising on the hill, in 2014 it’s a ramshackle mansion converted into apartments for an equally ramshackle collection of Indian residents, including a pair of feuding old ladies; a faded glamorous pianist; the mild landlord, Doctor, who worked in war zones; and Pinky, who is obsessed with romantic Bollywood movies. Taking residence are new arrivals: the recently widowed Bilal and his bookish teenage daughter, Sana.

In trying to find a “girl-shaped” place for herself, Sana stumbles on a hidden bedroom and a lost diary about a doomed romance that might unravel everything in both timelines. The diarist is Meena, a factory worker who captured Akbar’s imagination and threw the household into tumult when reluctantly brought in as his second wife.

All the residents are in some way haunted, but there are actual supernatural provoquants, too. Sana is tormented by the ghost of her once-conjoined twin sister who died after the surgery to separate them, and who reappears, like an especially malignant manifestation of teenage self-loathing, to voice her ugliest thoughts and ideations.

This ghost sister warns her about the djinn of the title, limping the corridors with a mangled leg and a broken heart, gnawing at its fingers. It’s a mute witness and memory keeper, drawn to the house from its centuries of worldly wanderings by Meena’s voice long ago. “You’re stirring up too many things,” her twin says. “It doesn’t like it.”

Neither does the house, the djinn’s more traditional ghostly counterpart, that lives and breathes: “The kitchen remembers the last time music from the record player filled the house; how the crabs had burned and the end had come so quickly,” Khan writes. As Meena’s diary catapults us toward that mystery, the house is unable to retain its secrets or its structure. “Pipes start to leak, cracks open in the walls, mold spreads and the cold becomes unbearable.”

Despite the Gothic trappings, this is not a novel of creeping dread. It’s rich and swoony, tilting for the ecstasy of Sufi poets like Rumi, with a wink to those epic Indian romance movies Pinky adores.

“Love in real life is an unpractical thing. It slows people down and makes their brains wonky,” Pinky lectures Sana. “Love is just for the movies.”

The author, like her philosophical teen protagonist, doesn’t believe that for a second. The love story at the heart of the novel is grand and gorgeous and brave. Sometimes, it’s a little flimsy, too.

One night, Sana finds Doctor watching an Indian masterpiece on his black-and-white TV called “Kaagaz Ke Phool,” a meditation on how fickle and fragile life is. The title translates as “paper flowers,” an apt metaphor for the rare instances where Khan’s novel (her first to be published in the United States) falters.

Though name-checked in the title, the djinn has little to do. Jahanara, the scorned wife, feels cartoonishly villainous. And as we race toward parallel endings, one shocking, the other predictable (with its own kind of satisfaction), we lose sight of Sana herself.

These are minor issues, however, in a novel that is an ambitious delight, with rich characters and some exceptionally lovely writing.

Here’s an aside you should know. Shubnum Khan is also the author of a book of essays, “How I Accidentally Became a Global Stock Photo, and Other Strange and Wonderful Stories.” When she agreed to be photographed for an “art project” without reading the fine print, it launched her as the face of hundreds of ad campaigns, for face creams in Turkey, carpets in New York and McDonald’s in China.

A decade ago, Khan’s photograph made her a sensation. I suspect her writing will do the same again. This is the start of a major career.

THE DJINN WAITS A HUNDRED YEARS | By Shubnum Khan | Viking | 320 pp. | $28