CHARLIE HUSTLE: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball, by Keith O’Brien

It isn’t easy mustering sympathy for Pete Rose. He was a compulsive gambler who bet on the team he managed, the Cincinnati Reds, then lied about it for years (he was also a compulsive liar). He had a sexual relationship with a teenage girl, and barely acknowledged the child he had with another woman out of wedlock. He was a self-pitying sore loser who abandoned friends once they were no longer useful to him, including the worshipful errand-runners who enabled his gambling habit. This is the Rose who emerges in Keith O’Brien’s new book, “Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball.” A mixture of disillusioned fan’s notes (the author grew up in Cincinnati, rooting for Rose during his prime playing days with the Reds in the 1960s and ’70s), investigative reportage and baseball history, the book paints a picture of an unchecked man-child with no desire to curb his appetites.

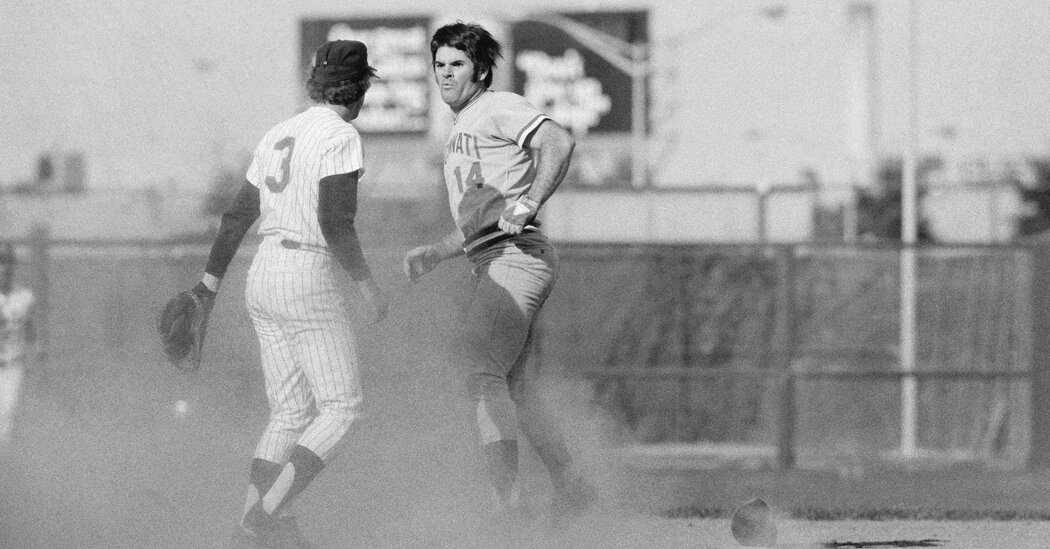

But that would make for a pretty boring story in itself, and O’Brien, who has previously written about the Love Canal environmental disaster (in “Paradise Falls”) and pioneering female aviators (in “Fly Girls”), is not a boring writer or thinker. Without overtly trumpeting his themes, O’Brien has crafted a sort of American tragedy about an undersized athlete raised to win at all costs, coddled by his blue-collar community, an overly accommodating press corps and fans won over by his all-out style of play. Rose was known for running to first base when he drew a walk and diving into the other bases headfirst (except in the 1970 All-Star Game, when he scored the winning run by plowing into catcher Ray Fosse, delivering a devastating shoulder injury in the process). Rose’s father was a Cincinnati semipro football legend who preached constant effort, and the son often seemed to be playing on the gridiron, not the diamond.

He could not admit defeat; this proved to be his fatal flaw when he stubbornly refused to acknowledge that he had bet on baseball. The league banned him for his sins in 1989; his dishonesty and lack of repentance made the decision a lot easier. By the time he confessed, the damage to his career and legacy was more than done.

Working with newly released F.B.I. files, “previously unutilized federal court documents” and more than 150 hours of interviews (including 27 hours with Rose, who cooperated with the author until he decided he didn’t want to), O’Brien tells a tale that runs on parallel tracks. One is Rose’s baseball career: his skill with a bat, which led him to break Ty Cobb’s career hit record in 1985; his pivotal role in Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine, which won the World Series in 1975 and 1976; and the nonstop way he played, which earned him the nickname Charlie Hustle. The moniker was conceived in derision, by the Yankee greats Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford, amused by Rose’s rah-rah play during a 1963 spring training game. Rose would come to wear it with pride.